There are many kinds of censorship, ranging — let’s say — from having a visiting His Very Rotundness Kim Jong Un with half a dozen goons with machine guns hovering over your computer when you work for a North Korean newspaper to our own inner fear of the possible consequences of expressing things in a certain way. “Will it hurt Grandma’s feelings if I say this?” may be enough reason to avoid saying it, or at least for trying to say it in such a way her feelings won’t be hurt. It could thus be argued that whenever there is some kind of expression, there is some kind of censorship.

Let’s focus on external censorship, then, of the kind that is conscious of its effect. Let’s posit a Grandma, or perhaps a Big Brother, who wants to actively hinder the expression of this or that.

It’s very common, these days, much more common than most people imagine. In Brazil, where I live, it’s enough of a reality that when I lost my column in one of the biggest and oldest Brazilian newspapers, a column I’d had since the ancient times when newspapers were printed and we had a set number of characters to fill each week, a friend of mine who works as a state prosecutor told me I was lucky, as I would probably be arrested if I kept writing about Brazilian politics.

I remembered it yesterday when yet another friend (a terrible and subversive activist, who fights the System as a Latin professor. Can you imagine the gall? To teach innocent people something as dangerously reactionary as Latin, of all things?!) asked me if I would translate what I wrote about the American election into Portuguese. He thought it might help people who only know what heavily censored Brazilian TV tells about the outside world. I told him I wouldn’t, not because it would get me in trouble — after all, it’s not about Brazilian politics —, but because nowadays there is no market for anything more complicated than celebrity gossip in Brazilian Portuguese.

And indeed. Today I paid more attention to the subjects presented in Brazilian news as I read it. Almost half of it was about the ENEM (more or less equivalent to the French baccalauréat or the American SAT; it’s a test people take after high school that determines one’s chances of going to college. The second day of exams was yesterday): questions that could be annulled because they had been poorly written, stories of people who arrived late or forgot an ID and thus could not take the test, this kind of thing. There were also a few titillating stories about lurid crimes. A few about the next Very Important Questions that will be judged by the Brazilian Supreme Court in the next few days. A single one about how the Brazilian president said Maduro was Venezuela’s problem, not Brazil’s. A smattering of translated stories from foreign (mainly American) news agencies.

This is what I found in a more “serious” news source, more or less the local equivalent of the New York Times. Others, more popular, will have little more than a few lurid crimes, lots of recipes, and tons of celebrity gossip. If I wanted to find hard news about Brazilian or international politics, I’d have to seek them in darker corners of the internet, in sources that the average citizen would hardly know existed. Well, in a way, the article about the Supreme Court is all the political news we need, as the Supremes have essentially replaced the Legislative and the Executive powers these days, ruling about anything and everything. They sort of legalized pot (carrying up to 40g is kind of allowed now), they legalized abortion, they forbade “gender” discrimination, they legalized “gay marriage”, and, much more importantly, they released former president Lula from (well deserved) jail and reinstated him into power. They own him. They rule.

The Supreme Court has also thrown a few journalists in jail for daring to publish stories they didn’t like. For good measure, they also locked up a few selected congressmen. Their supremacy is hardly contested nowadays.

But censorship doesn’t need to be that blatant to be effective. It can be argued that Biden was elected because the story about the contents of his son’s laptop was suppressed from American media before the 2020 elections. A few polls concluded that enough people wouldn’t have voted for him if they had known about it beforehand.

Good censorship — well done, efficient censorship — is discreet. Someone who has read Brazilian news every day for the last few years, growing accustomed to the increasingly smaller number of political news, will probably believe there were no print-worthy political stories to be published that day, and won’t think twice about their dearth. Likewise, the average Israeli doesn’t know much about what is still going on in Gaza. In Israel, Haaretz is what nowadays passes for extremist, almost treasonous, but compared to what we see in the Western press it is quite circumspect and strongly Zionist. That’s also my impression about Russia Today (RT), by the way: it is obviously Putinist and jingoist for Russia, but compared with, say, Sputnik, it is almost as if it tried to detach itself from too strongly pro-Russian opinions. Nevertheless, RT is as forbidden (as censored, as blocked) in Europe as Sputnik. The only way to read it is using a VPN to hide from censorship.

In the old days of the Brazilian military dictatorship, each newspaper had a guy from the Federal Police’s Censorship Bureau working in the newsroom, vetting all articles before they went to press. It was easier and cheaper to do that, as the alternative would be to have thousands of copies printed only to have them destroyed and another version printed if the government didn’t like something. Some newspapers would fill the blanks left by censorship with cake recipes so that readers would infer that the spot was supposed to carry something that was censored. It was a smart move, assuming the readers were also smart.

I sometimes wonder whether the editors of the “popular” news sources think the recipes they publish and the political news they don’t are a post-modern version of fighting censorship cake recipe by cake recipe, as in the sad old days.

I opened a Brazilian “popular news” source and screen-shot it so you, my dear and solitary reader, wouldn’t need to:

Above, the sum total of political news: “The [Brazilian] National Congress has greater control of the budget, compared to those of rich countries”; something about the President’s opinion on an unimportant aspect of online gambling; “Maduro is Venezuela’s problem, not Brazil’s”, says the President; and “financial markets project higher inflation for the 6th consecutive week”. It is followed by the horoscope.

The recipes, on the other hand, seem delicious.

Both screens carry ads for a money lender. For those who can read between the lines, that’s the real political news.

It seems like a nightmare for people who like to follow all kinds of political questions and meanderings but believe me, it’s much worse for those who used to write about them. However, that is not the point. The point is that this is what people see, and therefore it’s what they know and think about. In other countries, even if it’s not that in-your-face, it may not be that different if people don’t make a conscious effort to find sources. Or even if they do, as in the case of the Israeli censorship of Gaza.

While someone on this side of the Atlantic may perfectly well believe that there are no longer Israeli hostages being held by Hamas in Gaza, only rubble and dead bodies, up there in the Holy Land it’s not very hard to believe that Gaza is more or less intact, because after all the Army wouldn’t want to jeopardize the lives of the hostages. Short of using a VPN, just like your regular European who wishes to know what the Russians are saying, the immediate reason for much of the antisemitic outrages perpetrated around the globe today is hidden from the eyes of most Israelis.

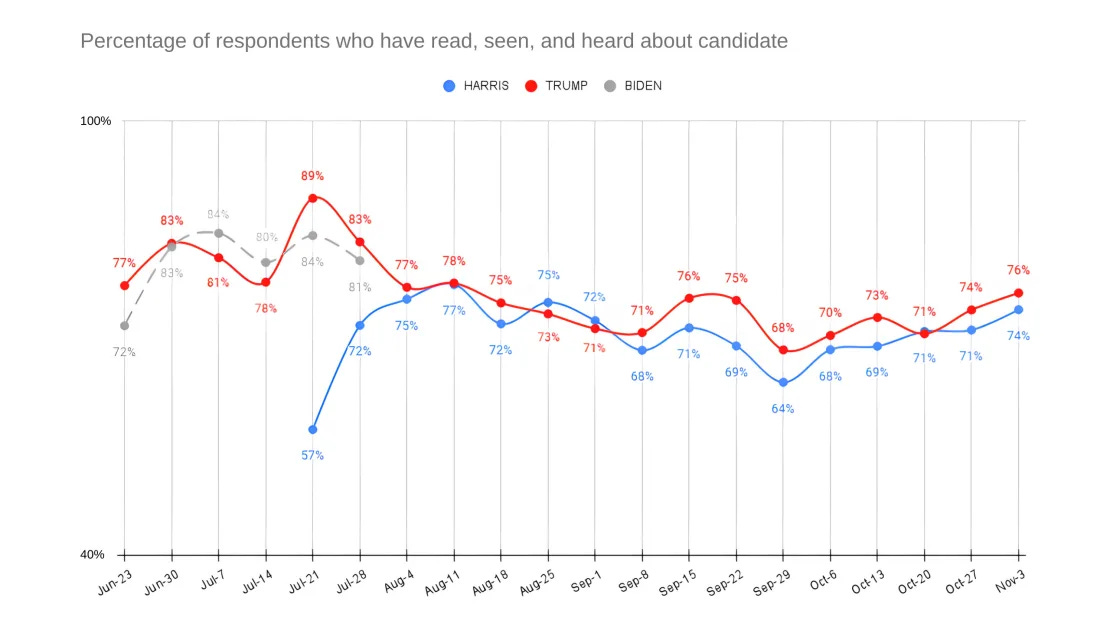

Even in the US, whose presidential campaigns were so omnipresent they invaded internet fora dedicated to inner questions of other countries, the average Joe, who is certainly not a Biden, doesn’t know much about anything. CNN published an article on what people heard about each candidate, and two things are evident: first, one in four Americans hadn’t heard a peep about any of the candidates in any given week leading up to the elections:

Second, those who did heard very little of substance (bigger words have been more widely associated with the candidates’ names):

When printed newspapers were replaced by online versions, one of the things that most annoyed me was that now we have a much harder time finding the news that will be important in historical terms. When I was a teenager, I used to go to the National Library to read 100-years-old newspapers for fun (yes, I was a weird kid), and from that experience, I learned that the things we find in History books much later were almost invariably buried in page 17b, while the front pages were filled with all kinds of stupid and sensationalist blather that had absolutely no importance in the long run.

It’s still like that, but when we bought a printed copy of a newspaper we had page 17b with us and it was only a matter of reading the seemingly irrelevant small news. Now, on the other hand, we have very efficient algorithms that make it much easier to find 50 different versions of the idiocies that would be above the fold on the first page of an old newspaper and much harder to find the things that one day will be in History books.

It’s censorship by algorithm, and it works even better when joined with the kind of censorship that kept the story of Hunter Biden’s laptop’s revelations hidden from the general public. That story was important for nothing less than the then-President of the United States and his whole party, and even then it was completely absent from most mainstream newspapers and virtually all social media networks. What stories are being hidden from us right now?

I don’t necessarily mean stories that will be very important in the long run, although they are of course included in the question. There are hidden stories that would be very important in the long run if somebody kept their memory alive, but that will have been memory-holed, just like in 1984. Many stories will remain unknown because they will have never reached the greater public. Some stories are as censored right now in the media of any supposedly free country as those that Brazilian newspaper editors would replace with cake recipes in the 1970s. However, unlike the latter, the former will not be talked about in newsrooms and filed for the day the dictatorship ended, as all governments and systems eventually do.

The internet made mass censorship much easier, even if at the same time it made it possible for small and unimportant publishers to reach a much greater number of people. That “much greater number”, however, will seldom be big enough to matter. Millions of uninformed people, whose view of the candidates was essentially what can be seen in the word clouds above, picked their candidates with less information than what I would ask for if I wanted to pick a dessert after dinner. And for them, it was OK, just as it is OK for nine out of ten Brazilians to have as “political news” the sheer nothingness I reproduced above.

To make things worse, the fleetingness of electronic data ensures that future researchers will have no idea about what was or wasn’t published or televised in our days. I wouldn’t be surprised if, in a few centuries, there were a dispute among historians of Italy about whether Georgia Meloni was indeed called “Meloni” or the word was a reference to her breasts, as she is the first female ruler of her country and a beautiful woman. All they will have to work with will be a few brass plaques here and there; all digital information will certainly be lost.

I have a few Zip disks with old backups that I would love to be able to restore, or at least access, but even if I could somehow connect a legacy reader to a modern computer, chances are I wouldn’t be able to read old file formats. We can multiply that by the trillions upon trillions of megabytes more often than not kept in “clouds”, that is, in computers owned by people who don’t care about the data itself, only about their contract with their customers. In computers whose contents will be impossible to parse when they are supplanted by something else, as they eventually will be. While the letters exchanged by a 19th-century writer and one of his friends may be found bound and kept in the attic of the latter’s family, my emails are bits and bytes probably distributed among several Gmail data centers around the world, and as soon as Gmail goes kaput everything will have been lost forever.

The only way to preserve digital data is to convert it into newer software formats every time the standard changes and save the converted files in newer physical media. An old Amiga text document I wrote in the late 1980s, for instance, would have to have been converted into a PC WordStar document, then into a Microsoft Word .doc document, then a .docx or .pdf file, going through several different kinds of physical media until reaching a modern thumb drive or memory card, and the process would have to keep going throughout the ages to keep it readable. Not even the loving offspring of a small author can be trusted to do that generation after generation to keep their ancestor’s “manuscripts” readable. And that’s if we assume computers will always exist, something I wouldn’t bet the farm on, the way the itchy fingers of those in power seem eager to press the red thermonuclear armageddon button.

Thus, digital information is in many aspects self-censoring across time. It depends on having the appropriate hardware and software to access it, and those change very fast. Furthermore, it’s virtually invisible. A Zip disk with silly cat pictures looks exactly the same as a Zip disk containing wonderful unpublished writings. Neither can be opened on a regular computer, anyway.

It is also self-censoring across space; an article being written now to be published tomorrow by RT or Al-Jazeera is already censored in Europe or Israel, as neither country will allow content from a censored source to enter its digital space. One can smuggle it with a VPN, but for most people, we could be talking about hacking NASA, for all it’s worth.

Finally, digital data is so vast it can only be navigated with algorithms, and algorithms are circular: if a person seems to like X better than Y, it will show more and more X and less and less Y. Applied to the news, it means not only that the algorithm will at the same time create and reinforce a bubble in which all the information will be from the same “side”, but also that anything that can’t be comfortably fitted within that “side” will always be hidden. Even if it would have been important enough to make the reader change “sides”, so as to speak, as could have been the case with Hunter Biden laptop’s revelations.

In many other ways, the gatekeeping of information has always existed. That’s why someone smarter than me said that if one can only read a single newspaper, it is better to read the opposition’s. After all, the situation has other means of making themselves heard. Likewise, newspapers have always preferred writers who could say the same thing over and over without seeming to repeat themselves, as most readers don’t like to have their certainties jeopardized by new ideas. A conservative newspaper always wanted its writers to spout the conservative party line, and a progressive newspaper would hate to see one of its writers refusing to follow the latest memo.

Algorithms, however, go much further than that in the censorship inherent in their vetting of sources to present, for one simple reason: algorithms don’t understand what they are doing. While a traditional human editor would consider whether the political consequences of publishing this or that piece of information would be good for his “side”, an algorithm will only consider an article’s origin, the keywords (or buzzwords, or dog whistles) present in it, and whether they are more or less present in the articles it has already presented its reader. New information or things that confuse the algorithm will prevent it from considering the (unread) article a good fit, and it will be made to disappear in the digital ether.

And it gets worse: AI (or Artificial Idiocy, for it has no intelligence) works more or less like present algorithms. Many of these already incorporate an element of AI. Unlike algorithms, that work negatively by vetting what will be shown, AI makes its own material. There are already AI-made playlists consisting exclusively of AI-made fake jazz on Spotify, for instance. It’s beyond horrible. It sounds like the mental image of jazz a teenager who only cares for hip-hop would have: plinking sounds seemingly produced by detuned pianos with strong echo effects that make them sound as if they had been recorded in a bathroom, repeating and repeating without a single beautiful turn of musical phrase, nonsense harmonies, the works. The beauty of jazz is a product of its complexity, and that’s why many jazz styles are rightfully seen as “music for musicians”: if you don’t understand what is going on, you can’t get most of it. What remains is what AI can reproduce: a nightmare soundscape of “soothing” sounds that could hardly be called music, and certainly could never be mistaken for the art of Bill Evans or Ben Webster.

Well, AI text is the same. It’s a distillation of “what worked” in algorithmic terms, a compilation of clichés that by definition cannot have anything new. The essence of mediocrity in the form of a text produced by a machine (an algorithm, in fact) that doesn’t understand what it writes, but is very good in identifying and reproducing mindlessly the worst of buzzword- and dog-whistle-filled hack writing. This kind of nonsense is already mingling with regular, human-produced, texts in algorithm-driven news selections. In other words, where there is news, there is AI-produced drivel. There is no escape. And it will get worse, especially because while a human writer will sometimes let an important bit of information slip, AI is too mediocre for that to happen. It can let bits of mind-boggling nonsense slip, but not real information, for the simple reason that it cannot understand a word of what it “writes”. It doesn’t write: it churns out moronic text-shaped babble.

But it will be good enough for lots of people, and that’s what is most scary about it. The 25% of Americans who didn’t hear a peep about either candidate in the weeks leading to the elections will find an AI-composed “summary” wonderfully informative. The majority whose total knowledge about the candidates consisted of the words in big letters in the word clouds I reproduced will find it perfectly OK. Meanwhile, important facts, all of them, will have been invisibly censored by the algorithms. There will be even more “news” articles published, but altogether they will amount to less than the Brazilian political “news” I pasted here. Algorithms have already replaced editors, and that is bad; they are on the brink of replacing writers. Soon there will be no more thinking people between the on-the-spot reporter, who more often than not doesn’t have the time, opportunity, or inclination to reflect on what he has seen, and the final (and first human) reader.

I have had some very good human editors, and it allowed lucky me to write and see in print a few things that made people think. It’s not the rule, but they were able to see that I was fair in my criticism of their “side”, and even that such criticism made my criticism of the other “side” stronger. In other words, they saw the consequences, not only the buzzwords.

Not all readers, on the other hand, were often that smart, to the point that for a time I would film and upload to social networks my assistant (who later became my daughter-in-law, but that’s a whole other story) reading aloud the comments people wrote about my column, often flabbergasted or doing her best not to laugh out loud. She wouldn’t read the comments before she was on camera, so as not to spoil her surprise. And surprised she would often be, as the depth of human stupidity is unfathomable. Some commenters would see in each and every criticism of their “side” proof that I was an extremist for the other “side”, while others would not even be able to understand there was some criticism there and responded solely to misidentified buzzwords. It was rather funny, and the short movies were very popular.

I have been censored, too, and quite a lot. After a “State Association of Transvestites” I had never heard about sued me because I wrote a few truths about the dangers (physical, psychological, and ethical) of “gender-affirming” medical interventions on children, I had to send my columns almost a week in advance so that the legal team could go through it with a fine comb, and I could be sure that anything that touched matters of “gender” would be spiked. But then, they were paying for my defense, and lawyers are not cheap. A few other articles that stepped on too many and too important toes got spiked, too, but since the beginning, they had asked me to always keep two pre-vetted atemporal texts available for publishing. The news business is a business, after all.

Adding all of that, both from my personal experience and from my limited knowledge of how digital data is handled, I see the present situation as dire, that of the near future as even worse, because of AI, and that of the distant future, as I wrote above, as a time in which our age will be seen as a temporal black whole from which almost no information will remain. The strongest possible form of censorship.

Nobody really wants to hear about anything they don’t already know and agree with. It’s very unsettling to hear another point of view, so we choose to live in echo chambers. And governments want us to live there too.

Elon made a point that we should have AIs that are “truth seeking” but that’s a fantasy really.