Artificial idiocy

and real intelligence

“Artificial intelligence”, having trickled out of the realm of software-development labs, has been everywhere in the media. From AI-generated answers that could pass tests to amazingly complex images produced by natural-language prompts, things are going so fast that if one believes the media the Terminators will be arriving to hunt us all down sometime next week. There’s only a very small snag in all that story, even if we do believe the Terminators are arriving: while it is “artificial”, that is, a technical construct, that thing has nothing to do with intelligence.

Intelligence is quite hard to define; I, for one, do believe that IQ tests, for instance, are a great measure of one’s ability to perform well in the kind of tasks measured in IQ tests, and no more. On the other hand, it is not that hard to see that some people are much brighter than others, even if their brightness is focused on very different things. I’d venture to say that the common trait of intelligent people is the ability to trace connections other people can’t see. It may be joined to the ability to imagine 3D stuff and make a good engineer, or to an interest in why and how people behave this or that other way and give society a good psychologist or sociologist. But the basic ability to connect previously separate dots is indeed the trick.

Artificial “intelligence”, on the other hand, is just a (very) vast and (very) fast encyclopedia of pre-determined patterns. In technical terms, it is fantastic at formal logic, but utterly incapable of material logic: it cannot understand anything, but it can re-use all kinds of patterns it has been exposed to in its training. That is why a few years ago, while it was still something in IT labs only, its trainers were worried it sometimes sounded racist; garbage in, garbage out, and racism in racism out. All it did was finding not only the more-or-less evident patterns of open racism but also the more subtle and indirect ones. If scholastic tests measure studying ability and a certain group of people supposedly need easier tests or different tracks into college, the premises are there for the formal-logic machine to provide the hidden corollary: that group of people has lesser studying ability. It is not necessarily true; their lack of academic (unaided) success can come from plenty of other roots, such as a culture in which studying hard is not perceived as a good thing. But as the pattern was there, even if it could not be mentioned, the machine connected the dots, without knowing what the dots were.

The dumb machine cannot even start understanding either racism or cultural differences, as the only thing it can do is pattern recognition. Formal logic. It can not even understand what a test is or what a person is, much less the emotional elements of passing or failing tests, the cultural and psychological reactions one has to scholastic success or failure, and so on. It can “see” that some words are associated with others, even if the association is unconscious or hidden for political reasons, but every single word it perceives to be patterned together with others, every element of its logical calculations will be a flatus vocis, a meaningless and empty symbol.

It is a tad easier to see it in realms other than text. AI-generated visual “art”, for instance, is interesting in what it can do and fascinating in what it gets wrong, for the latter shows much more clearly it is not “intelligent” — that is, it cannot understand, it has no intellection — at all. For instance, one of those oh-so-praised AI graphics-generating software is defined as such:

DALL·E 2 is a new AI system that can create realistic images and art from a description in natural language.

For it to be true, the definition of “realistic” would have to be stretched beyond all credibility, because all it does is try to reverse-engineer the natural-language prompt. In other words, it produces an image that — according to the patterns it discerned in bazillions of images and their descriptions — would be described by the prompt given it by a poor son of Adam. What it cannot do, though, is understand that image. Drawing human hands, for instance, while challenging to a (human) beginner artist, is a much greater challenge for AI systems:

It happens because it cannot grasp (pun intended) what a hand is; perhaps in the near future that particular problem will be “solved” by, for instance, forcing the systems to perceive the basic patterns in hands (their parts, articulations, and so on), just the way the much simpler task of face recognition is “taught” them. Nonetheless, it will still be a formal, not a material knowledge of hands.

So the images it produces are similar to what has been described as “realistic” in the images used to train it, but they will never be “realistic” in the strict sense, for reality is something it cannot know or understand. They may please the eye, indeed; probably much more than the “art” of the vast majority of mediocre or plainly bad “artists”. But realistic it cannot be, just like Max Martin cannot become Beethoven or Mozart. If the latter two were great chefs, the former (who wrote more Billboard singles than Michael Jackson and Madonna combined) would be a bubblegum factory. And AI “art” is a kind of bubblegum, for it lacks that crucial element that defines intelligence, which in musical terms all great composers (even pop ones, such as Cole Porter or the Beatles) had: that capacity of seeing (musical) connections that are invisible to everybody else.

AI can only discern patterns that are already there because it cannot understand the dots the patterns connect. It cannot understand either an adjective (such as “sad”) or the thing it describes (the person feeling the emotion triggered by a minor chord, or a tragedy, or a great loss). It can only know that the flatus vocis “sad” and the flati vocis “minor chord”, “tragedy”, and “great loss” usually appear together.

It is, however, much in the spirit of our times. Almost one hundred years ago, Ortega y Gasset wrote an essay on what he called the “dehumanization of art”. His quite interesting point — a connection nobody else had made; he was a very intelligent man, after all — is that before Modern Art arrived art was by definition something human, that is, something that pulled at strings all human beings have, but Modern Art made it about a certain “secret code”. An artificial artistic language one has to learn in order to understand and appreciate. Cubism and dodecaphonic music do share this same trait; they are, like beer or sushi, an acquired taste.

I have an interesting anecdote about this “secret code” thing: my aunt studied Fine Arts and became a successful industrial designer in the 1970s. In the 1980s, she accompanied her husband, a telecom engineer who worked for the government, on a business trip to Japan. Their hosts, eager to please the important wife of the important technical representative of a foreign government, had prepared her a schedule similar to those that had worked with all previous important wives of important people from abroad: shopping malls, electronics stores, and so on. She was horrified, as she had absolutely no interest in electronics (she could not even use one of them newfangled hand calculators, then a brand new kind of gadget). She wanted to see Japanese Art, with a capital “A”. So the poor guys, all sweating and bowing profusely, took her to some Art museum. She saw plenty of regular stuff, until all of a sudden she saw a (Modern) painting and said “now, that is GOOD.” Her guide told her it was by the greatest Modern painter in Japan. As she knew the secret code of Modern Art, she could identify the “GOOD” stuff, even in a place where she had no other cultural frame of reference.

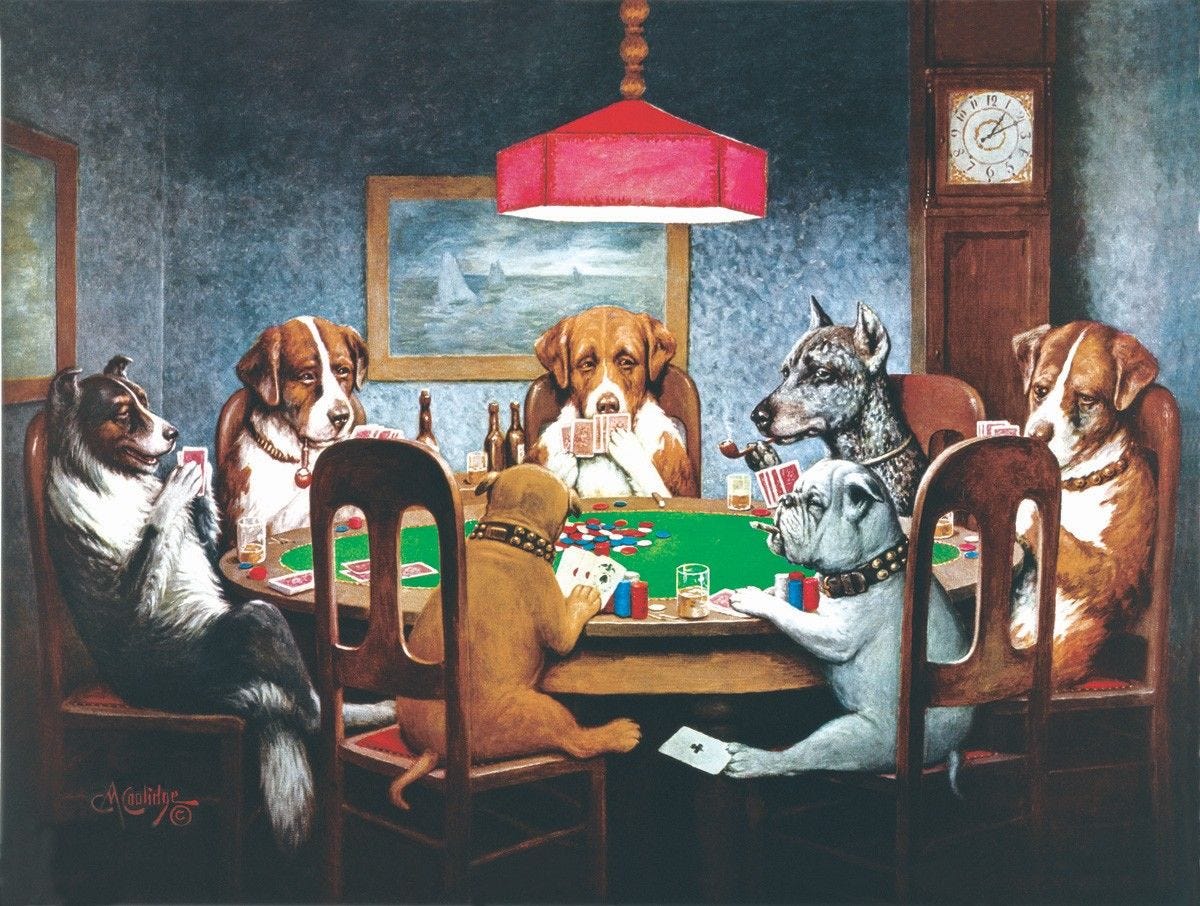

Now, what is the main difference between the first painting of a young lady and the last painting, of dogs playing poker? Both are similar in that both are made to be seen and understood by any human being, and that sets them apart from Picasso’s young lady. There is no previous knowledge needed to understand them, unlike with the second painting. But immediately after that first and universal frame that makes both available for our understanding, there is something that is sorely missing in the dogs’ image. That “it”, that je ne sais quoi, is what makes Art with a capital “A”. Bouguereau was an artist (even if at his time he was accused of being a pornographer); the dogs’ painter an artisan. Both knew the medium they used. Both could draw, and both knew where the shadows should be and how to reproduce them. But the latter could not go further than that first impression, could not do more than put a describable idea on canvas. According to a prompt, just like AI, but from a human sensibility. And it makes quite a difference.

For those who would unironically hang the poker-playing dogs on the wall, on the other hand, the main difference would be the subject matter of the paintings. The first “is a young lady”, and the last “is a poker game between dogs”. Neither is more than what is represented, neither is more than the subject matter. The same person who bought the dogs could, however, buy the young lady, because she is beautiful. She, not the painting.

The availability of that first level of perception is what is missing in Picasso’s young lady. I’m not saying it is ugly, see. I’m just saying that it cannot be understood as beautiful, or even as a young lady, by the uninitiated. It’s not for the great unwashed.

Now back to AI-generated “art”. It is much farther from Bouguereau than the dogs, because not even the human element is there in a direct form. It is there only as a reproduction of patterns that were commonly associated with the flatus vocis provided by the human user as a prompt. It cannot differentiate between the schmaltz and the beautiful, because it cannot understand what beauty is. In fact, it cannot understand what anything is.

If we changed art forms, one could say that while the first young lady would be a lively tune by Tchaikovski, the kind one keeps absently whistling, the second would be some dodecaphonic piece only the initiated can appreciate, and the last a crude stomping music drunken men would dance to on their day off. But none of them could be produced (as opposed to reproduced) by AI.

AI-generated art, in a way, is like Modern Art, insofar as it is filtered — and very remotely filtered at that, as it cannot even see its own product. For the generating software, the result produced is just a combination of pixels that is usually patterned together with the words in the describing prompt. The difference is that it tries to hide the secret code, in a way, for it literally consists of thousands of lines of computer code trying to mimic an image that would be described by the prompt. It can produce “a young lady” in the style of Bouguereau or Picasso, or even photo-realistically, just as it could produce an image of poker-playing dogs. But it cannot (for now) understand that young ladies’ hands tend to have five fingers, and will never be able to understand that young ladies exist and can be gorgeous creatures indeed, so gorgeous even the Holy Ghost married one of them.

This kind of pattern recognition followed by pattern reconstruction cannot in fact produce anything new, because it can only re-produce patterns, even if they are rearranged over and over again according to unfathomable lines of code. It cannot trace new connections; it cannot even deconstruct a young lady as Picasso did, for he was the first to do that precise deconstruction. He took African masks and rearranged them, producing something new, that his followers could decode as beautiful. But to do that, he had to understand what makes a young lady, what makes an African mask, and what he could take from one and the other. He had to create a connection nobody had created before, while AI can only apply the connection he (or any other painter) made in order to simulate, to make a simile, of his peculiar style.

The dehumanized art of Picasso still needed something human, the intelligence that is conspicuously lacking in computers. Likewise, AI can probably compose dodecaphonic music, and even dodecaphonic music that sounds better than the original stuff (it is not that hard), or, conversely, that is even more grating for ears that do not know the code. And it can certainly compose enough easy listening muzak to play without stopping or repeating a theme in all elevators and dentist offices around the world until the end of time.

But it cannot know what it is doing, for cannot know what are the dots in the patterns it recognizes and reproduces, and thus it certainly cannot purposefully create anything really new. Because it is not capable of intellection, it cannot form new connections. Because it cannot recognize beauty when it “sees” it (in fact it cannot see anything!), it cannot create real Art. It may, in a very limited way, have Picasso’s code, but it does not have the human code. Without understanding something one can only parrot it, and AI is just a very good and very fast parrot.

That is what makes it so adequate for the spirit of our times, in which quality has already given way to quantity in all domains of human life. Or at least in all those that can be reduced to bits and bytes, therefore simulated by AI. Just like a couple of hundred years ago weavers and their handlooms gave way to industrial-scale steam-powered looms, and nowadays clothes from China are cheap enough not to be worth fixing tears and such, the poker-playing dogs’ painters and the people who write the nonsense that keeps people reading clickbait listicles for long enough to see plenty of ads, as well as the Max Martins of this world, will be replaced by AI-generated simulacra.

Content-selling is where the big bucks are at these days, and the quality of the content is at best an afterthought. Vasts amounts of terabytes are streamed to be rendered as “music”, text, whatever, in our phones and computers. Pretty little of this has, or has to have, any quality. Even the music that is most expensive to record (not to mention the long hours stretching into years of a studio musician’s training) has its audio recording compressed until everything sounds the same, so that it can be listened to in cheap earphones or a cellphone’s tiny speakers. Digital influencers sell their shallow personas in lieu of any real content. And so on; quantity, not quality, is the name of the game.

In this context, it makes plenty of sense to substitute AI-churned garbage for human-generated garbage. If there is no market for art, but there is a vast market for content, artlessly AI-generated content is indeed the best option.

It would obviously be better if there were a market for real Art, as that is the precondition for its production. The so-called Renaissance gave the West a stupendous amount of great Art because there was a colossal amount of money burning holes in the pockets of people who directed some of it to starving artists. Without it, they’d have starved. Later, a prodigious amount of written garbage was produced when printed newspapers democratized the consumption of written text. From that garbage a few pearls were saved, people who wrote one day what would be wrapping fish the other, but who had that je ne sais quoi, that talent, that intelligence that AI cannot have. And thus we have, for instance, Dickens, Dumas, or even Chesterton.

Unlike a newspaper, which would have a few copies preserved in libraries, however, digital data is at once ephemerous and — for being infinitely multipliable — unkillable. Perhaps stuff good enough to be worth preserving will indeed be, together with the digital equivalent of dogs playing poker or crying clowns. Perhaps some beloved human-written books, even if published only in ebook form, will be transported from legacy data formats to new ones, from one kind of media to another, until the time comes when their real worth is more widely acknowledged. And perhaps, even, as with the proverbial thousands of monkeys with typewriters, something good will come out of AI.

It would be an accident, though; Terminators are way more probable.

![Vendangeuse [The Grape Picker] Vendangeuse [The Grape Picker]. The painting by William-Adolphe Bouguereau](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Ql6U!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa6a19841-41f3-4955-9517-82732822b025_430x700.webp)