One of the saddest phenomena today is the worldwide uniformity in clothing. While less than a century ago the clothes people wore were typical of their society — to the point that a serious researcher can tell the national origins of immigrants in old pictures just by looking at their clothing — nowadays just about everybody dresses the same, all around the world. Blue jeans, sneakers, and a t-shirt became a kind of uniform everywhere weather does not force people to wear heavier stuff. And even the heavier stuff is quite uniform all around the world.

It is only the visible tip of a vast social iceberg of uniformity. While there obviously are cultural distinctions that remain more or less as strong as they used to be, the Modern steamroller does what it can to efface not only cultural distinctions such as those that used to be seen in clothing but also individual characteristics. Modernity wants everybody, everywhere, to be (or to become) Mr. Regular Guy. His “regularness”, though, comes from the assumptions Modern philosophy makes about people, and most of them are wrong. After a couple of hundred years of forced uniformity, those who had the bad luck to be born in thoroughly Modern societies (what used to be called the First World, and now refers to itself as The West) are, evidently, much further advanced on the path of national- and self-erasure. The worldwide uniform of sneakers, jeans, and t-shirts, though, shows how strong this collective philosophical effort towards uniformity still is.

There are still some kinds of clothing that remain in use, especially when the weather makes them a much better option than the Modern uniform. The delicate and thin fabric of several kinds of “typical” baggy clothing, for instance, makes much more sense in hot climates. Not that common sense has much to do with it; after all, wearing jeans only makes real sense when one is a manual laborer, rides horses or bikes, or somehow else needs to wear abrasion-resistant clothes.

(disclosure: I do wear jeans for the very same reason I am complaining about: it has become “the regular” clothing that will not attract attention anywhere. As I have absolutely no interest in fashion or clothing apart from the sociological perspective, I own six pairs of jeans and six black polo shirts, and that’s it. When I need to buy clothes I just go to a store and ask whether they sell stuff just like what I am wearing, and buy half a dozen. I can dress in the dark, and I still know how to ask “do you have one just like this one” in the languages of all the countries I’ve lived in.)

In a way, the social history of the Modern uniform is quite interesting in several aspects. Its first iteration was the bourgeois black suit one can see in old Dutch paintings. That suit was the by-product of sumptuary laws and restrictions on the dressing of commoners. If you were born in the right (noble, that is) family, you could wear fluffy lace. If you were a commoner, no matter how rich, you could not. You could still ride a horse, though, just like nobility. It made sense to imitate the clothing of nobility, minus the lace, and wear suits and pants instead of the robes poor commoners would wear. Riding in a robe must be an awful experience.

Drab versions of nobility.

The blackness of that first bourgeois “uniform” was the fruit of both restrictions on colorful stuff for commoners and (Calvinist) religious restrictions on anything that seemed fun or beautiful. Catholic priests wear black cassocks because they are “dead to the world”; Calvinist businessmen wore black suits for quite similar reasons, even as they worshipped Mammon rather than the Christian God.

As Modernity make Mammon-worshipping a source of pride, not of shame anymore, what came to be known as the business suit became widespread. In a sad reversal of what happened before, wearing a dreary suit became the hallmark of a new élite, a new “nobility” that based its claims to power on money, no longer on its vows to protect the poor. In fact, they would much rather fleece and oppress the poor than protect them. The situation grew worse and worse until by the end of the XIXth Century both Marx and the Church recognized a huge social problem and wrote about it. Marx wanted the proletarians (that is, those whose single economical good was their children — and the kids’ labor) to revolt; the Church called the businessman to ally themselves with the workers, just as in previous and more civilized times nobility and commoners would form a society based on personal vows.

The funniest thing about that reversal of clothing codes is that the poor became much better dressed than their oppressors, as they were the ones who kept dressing the old way. They wouldn’t have the gorgeous outfits of the old nobility, of course, but the very lack of uniformity, together with the use of what color they could get, granted them a much better look. In a way, that is still the situation in most of Africa: the dictators and their folk wear business suits, while the “commoners” wear gorgeous colored stuff.

(full disclosure: I still own a couple of suits. I seldom had to wear them before retiring, but sometimes I could not avoid it. The only time I wore one after retiring was at my son’s wedding.)

In a way, it is quite interesting to notice how — after the supernatural aspect of Calvinism gave way to its immanent money-grubbing character, giving birth to Capitalism, and that “dead to the world” stuff got buried together with the fire and the brimstone — the subtle possible differences in business-suit-wearing became important. The color and shape of the ties, for instance, tell nowadays more than much of the richly decorated details in the colorful clothes of ancient nobility. Likewise, the way an expensive suit fits the body (and hides the prominent belly of a successful businessman) marks its owner as a true member of the “real” new nobility today.

Here in Brazil, when the military dictatorship imported American Pentecostal preachers to fight the Church (the generals did not like the way the clergy condemned from the pulpit their worst human-rights abuses), the new sects imposed “business” attire for their followers. At the very beginning of this religious colonization, the poor who joined the new sects wore suits in more or less the same way a member of an old penitential society would wear a cilice or a public sign of penitential devotion. Together with the suit, the new religions brought other strange marks of belonging, such as forbidding their lady members from cutting their hair or wearing make-up or jewelry, and these were also read by their native devotees as visible signs of penitent living. Later, when Brazilian preachers were formed by the American imports and (as predictable) started their own new religions, vaguely based on what they had received from their American teachers, the general demand of wearing a suit was replaced; now the preacher is the one who wears them, and a very badly-tailored business suit became the standard clerical attire of Pentecostal preachers. With the exception of a few rigorist sects, many of them still connected to the original American ones (such as the Congregational denomination), the rule now is to have a guy in a suit yelling at a microphone, and jeans- and t-shirt-clad followers singing, paying tithe, and getting possessed by (quite unholy) spirits.

When Modernity formed its new nobility and informed it with its sartorial and psychological uniformity, it was just the first step. Uniformity, after all, is one of the essential characteristics of all forms of Modernity, which began with the assertion of the universality of Reason. God (and therefore religion) became a private and non-universalizable matter, but Reason, with a capital “R”, took His place. When the French revolutionaries crowned a naked prostitute as the “Goddess Reason” atop Notre Dame’s main altar, they were not joking. Reality gave way to ideas, and (supposedly rational) ideologies became the new gods. All ideologies presuppose the universalness of their application, and, in turn, this universal application presupposes the uniformity of minds and wills.

The bourgeois élite, with their sad business suits and their full control of the economic (and later financial) levers of society, was but the shock troops. The avant-garde of an ideological “progress” towards a fully-uniform society. When it was possible, drab uniforms were imposed on the employees of big businesses. The same happened to armies, as Modern conscript armies had no room for the heroes and berserkers of old. The first army uniforms were still beautifully colorful (as that of the British “redcoats” by the time of the American Revolution) because it was easier to grab conscripts if they could be made to dress like the ancient nobility. They were, nonetheless, uniform. One soldier could not be differentiated from the other, even if any of them would look good at the local brothel for a little R & R. Later, the same “progress” towards drabness, further added by the rational need to conceal soldiers in the field, led armies towards green or khaki uniforms, later followed by their camouflaged versions.

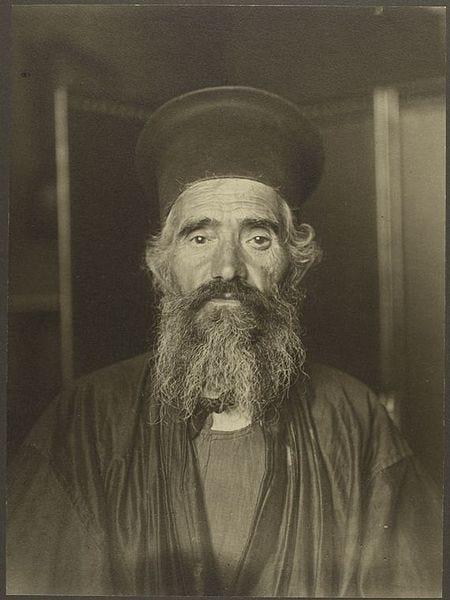

Most of the poor, nevertheless, still dressed beautifully and according to the age-old traditions of their people. The photographs taken by Augustus Frederick Sherman at Ellis Island, roughly one hundred years ago, show us the beautiful and varied clothing in which immigrants from every corner under the Sun arrived in New York:

(Algerian young man)

(young lady from Alsace-Lorraine)

(Dutch kids)

(Father Joseph Vasilon, from Greece)

There’s even a book with these pictures, for those who want to dream about a saner world. Sadly, the descendants of the people portrayed there are probably wearing jeans, t-shirts, and sneakers somewhere in the United States by now. Much has been lost when true differences were erased to make room for Modern uniformity.

And now, after seeing the twists of history around the uniform of Modern (business) nobility, we finally arrive at the Modern uniform for commoners: jeans and t-shirts. Jeans used to be working clothes, and t-shirts were underwear. As Modern society, with the help of public schooling and advertising, managed to impose some uniformity of culture and mores, along with it came the destruction of that last visual bastion of civilization: the clothes of the poor. The humiliation of walking around in one’s underwear (t-shirts) is thinly disguised by their function as billboards for (supposedly individual) statements and images that pretend to make up for the lack of real cultural cohesion one would see in the old ways of dressing. Likewise, having the poor wear working pants even on their days off is in a way akin to the harsh rules of earlier Modern armies forbidding soldiers to wear civilian clothes even on their days off.

Those wearable flags of one’s culture, that we now call “typical” dress, however, in a truly Modern fashion (pun intended) were replaced by individual marks. Permanent ones: tattoos. In our present (Post-, or Hyper-)Modernity, the drabness of uniform clothing — almost as awful as when the Chinese could only wear Maoist uniforms — leads many to remake their own identity through body modification. There is, of course, a vast spectrum of possible modifications, with a hairdo at one end and the “serious” stuff some crazies do (forked tongues, horn implants, whatever) on the other. Getting a tattoo used to be quite a radical and anti-social thing to do, but in more recent years it became more and more mainstream. In some rather sedate milieus these days, not being tattooed is stranger than having what, from a distance, always looks like a bruise.

Those being tattooed frequently believe they are asserting their individuality, their difference. It is seldom the case; not only are their tattoos usually picked from a catalog, but few have anything to “say” with their tattoos that has not come ready-made from media and advertising. Even their notion of individualness and difference is usually a packaged consumption product, part of a ready-made identity kit that determines the music one will listen to, the films or series one will watch, and so on.

It goes quite well together with the jeans pants, the t-shirt, and the sneakers. Especially as the brands and models of the sneakers, jeans, and t-shirts worn will usually be also parts of the same identity kit.

In our current degenerate Civilization the organization of Slavery does not allow for the use of regional clothing. Only for very specific events are the Old/Tradicional garments used. In many places they just exist in Museums.

Another evident reason for this is that if you're from Herd A and move to the region of Herd Z you'll want to avoid being noticed! It's like the black duck...

We've been programmed to look with suspicion to what is DIFFERENT (specially to those things not sanctioned by the STATE).

And if you move to the region of Herd Z naturally there aren't any modern slaves producing the tradicional garments of region A, and since you probably are not able to produce your own garment, you can only BUY the stuff that's available around the Planet! Jeans & T-shirts Inc.

If They decide to stop manufacturing Jeans due to Climate Change (just like They are doing with ICE vehicles) you, and I, will start wearing what They want! Unless you learn to make your own garment!