When I see the way people treat “Artificial Intelligence” (henceforth AI, which, as I already wrote, should be “artificial idiocy”), what really scares me is how often people perceive it as if it were a kind of superior intelligence. Just like the fantasies of hyper-technological aliens, by the way; the only difference is that AI is here, while said aliens are not that much.

But I shouldn’t be surprised, for one simple reason: AI is just a reflex of the societal situation in which urban people in rich countries (or in the richest enclaves of not-that-rich countries) spend their lives.

That global minority lives in completely artificial environments, whose temperature is controlled, whose food comes in clean boxes, often in ready-to-eat form, whose (treated and bleached) water flows on demand from every tap. Their jobs consist of moving a mouse and clicking a keyboard while watching intently a screen; their relaxation, on the other hand, consists of watching a different screen, without clicking a mouse or moving a keyboard. For them, the easiest way to know if it is raining is also through a screen. They can spend years without seeing the moon and their whole lives without seeing the stars.

It’s not their fault, of course. That’s the world in which they were born and raised, even if it is more akin to a mid-20th-century dystopic sci-fi space mining base than to what any of their distant ancestors would be able to recognize. The skills that any person would have had in any other historical period — making fire, riding a horse, cooking, mending clothes — are completely unknown to them unless they pick them as hobbies. The stars in the sky that mesmerized virtually every human throughout history are also not part of their experience. The phases of the moon and the way the place where the sun rises and sets change throughout the year are also academic knowledge without any relationship to daily life. In Gn 1,1:14, “God said, Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days, and years”. For 21st-century urbanites, however, that’s what clocks were made for. What would lights on the firmament have to do with time?

It is so because the Modern worldview completely separates man from the rest of Creation, and not in a good sense. By opposing man and “nature”, the rest of Creation (we are not unnatural, even if our society is) will be seen as either resources to be extracted and destroyed for gain, or as somehow “better” than us, thus making man a plague inflicted upon it. Both sides, of course, are wrong, and both agree in much more than they would realize. Just for a start, if man is one thing and “nature” another, it makes sense to separate one from the other physically, not only conceptually, and lock everybody in climatized apartments and cars away from a “nature” that is a threat to us or threatened by us. In the end, it’s the same if we stay in artificial environments to protect us or to protect “nature”: unnatural environments make us less human.

One of the saddest ironies of these God-forsaken days is that misogynists, with their talk about different-colored pills, seem to be the only ones to remember the awful Gnostic movie trilogy that was a box-office hit around the turn of the century. In The Matrix movies, the hero discovers reality to be a simulation. Straight Baudrillardian nonsense, but at the time it seemed edgy. Now, however, people are saying the whole universe would be a simulation of sorts. Something quite easy to believe when one lives in such an artificial environment as that of rich urbanites, from which almost everything that would force us to realize the real-ness of the world is expunged through technical means, ranging from pain-killers to pest control and climatization.

Just like the man who preferred his milk to come from a clean store rather than from a dirty cow, we keep time with clocks instead of lights in the firmament of heaven. What most fail to realize is that the clocks are just machines that reproduce the movement of those lights and show them in a way that is easier to read. In other words, we mistake the symbol for the thing symbolized, as someone who would mistake a stick man for a living and breathing human being. The same goes for most of what makes urban living: climatization is an artificial indoors simulation of a pleasant climate, for instance.

In other words, while we don’t live in a simulation, as The Matrix would have it, our society does its best to make it so. Even our screens, such as that in which you, my solitary reader, are parsing the pixel-formed characters that simulate a page from a book or a magazine, are sources of simulacra in which we spend much more time than we did when the first The Matrix movie was released.

Now, what is a simulacrum, and what is the difference between a simulacrum and the real thing?

In Aristotelian-Thomist metaphysics, we have a few concepts that can help make it clearer:

A substance (from the Latin for “being under”) is what a being is. It’s the answer to the question “What particular being is it?” I am a substance, you are a substance, this glass of water is a substance, that house is another substance.

An essence (from the Latin for “quality of a being”) is the nature of a thing. It’s the answer to the question “What is that particular being?” A horse will have an equine essence, as you and I have a human essence.

An accident is something that only exists in other things. For instance, colors, size, and so on. Nobody ever saw the color yellow by itself; we only see yellow things. Nobody has ever seen a centimeter or an inch, only things that measure one or the other.

A note, finally, is that by which we recognize something. For instance, the notes of a horse are quite similar to those of a zebra, but the zebra’s black-and-white pattern is unmistakable. Likewise, we can easily recognize our friends and relatives by their appearance, voice, etc. In other words, notes are the accidents that lead us to recognize the essence or substance of something. This word is the root of the terms denote and connote, respectively meaning “from [that] note” and “with [that] note”.

Accidents change, though. When we see a grown man whom we only knew as a young boy, we most certainly will not recognize him. Sometimes they change fairly quickly: my brother-in-law, when he was a kid, was very fat. Nobody knew it at the time, but it was because of a chronic pancreas problem that eventually evolved into an acute pancreatitis, which he fortunately survived. After he healed, he lost all the extra weight and had a spurt of growth, and when he visited us, a few months later, my wife didn’t recognize her brother until he called her. She was expecting a short and fat kid, and was met by a tall and gangly teenager. In other words, the notes were all wrong, but the substance — that one person, her brother — was the same.

A simulacrum, then, is something whose accidents simulate those of something else. Anything we see on a screen, by definition, is a simulacrum made of pixels, tiny red, blue, or green lights that go on and off in such a way our eyes mistake them for something else — the face of the person we are video-calling, for instance, whose colors and dimensions are being captured in real-time by his camera, translated into binary digits, transmitted through electric or optic-fiber cables or radio waves, and simulated at our end on our screen.

A horse could be painted to resemble a zebra or vice versa. Hollywood make-up artists are very adept at making one person resemble another. Trompe l’oeil (“fools the eye” in French) is a painting technique that can make wood seem to be stone or stone, wood. Fake silicone breasts and botox are used to simulate some notes of youth; of course, other notes cannot be simulated, hence the uncanny-valley vibes of many older ladies nowadays.

In other words, simulacra are all about accidents. They superpose the accidents that are the notes of one thing on another thing, so that we mistake the latter for the former. Blinking pixels on a screen are not Tom Cruise hanging from a flying plane, even if they simulate it well enough for us to enjoy the movie. A zebra may be painted brown, but it won’t make it adequate to ride. A 50-year-old woman can spend a million dollars on plastic surgeries and beauty treatments, but it won’t make her young again.

Our society pays extraordinary attention to accidents, and almost completely forgets about essences or substances. That is why it can even pretend that a few surgeries and regular doses of hormonal poison can make a man into a woman or a woman into a man. It makes even less sense than trying to make an older lady be twenty again. After all, the lady was once twenty; she is trying to change her present accidents into those she had a few decades ago. The substance is the same, her female essence is the same. But a man is a man is a man, and, in the immortal words of Tom Jobim, “women are a different beast”. Another essence, that might be more or less successfully simulated, but not changed into.

AI is also all about accidents, even more so. It only deals with symbols, and symbols that are completely void of any underlying reality. They are not symbols for other things, as far as AI is concerned; they’re empty symbols, like those on a deck of cards. Tabletop games are usually a ludic manipulation of pure symbols; often, people will use matchsticks or beans as symbols for money — something that is already a symbol, by the way, as banknotes have no worth on their own. A card that may have this or that value in a game has a completely different value and function in another. It’s not even a simulacrum; it’s sheer symbol-manipulation.

Life, however, is not a game, nor are we or all that surrounds us mere symbols. Even while we plunge into simulacrum after simulacrum at work and home, staring at pixels all day long, we still have to eat, drink, go to the toilet, sleep and wake up, shave, get dressed and undressed, do the laundry and the dishes, and so on. In other words, we have to deal with reality.

Even a tame reality such as that of urbanites, even a reality of such artificialness, demands its pound of flesh. That’s why older ladies try to convince the world and themselves that they are twenty again: it’s not pleasant to get old.

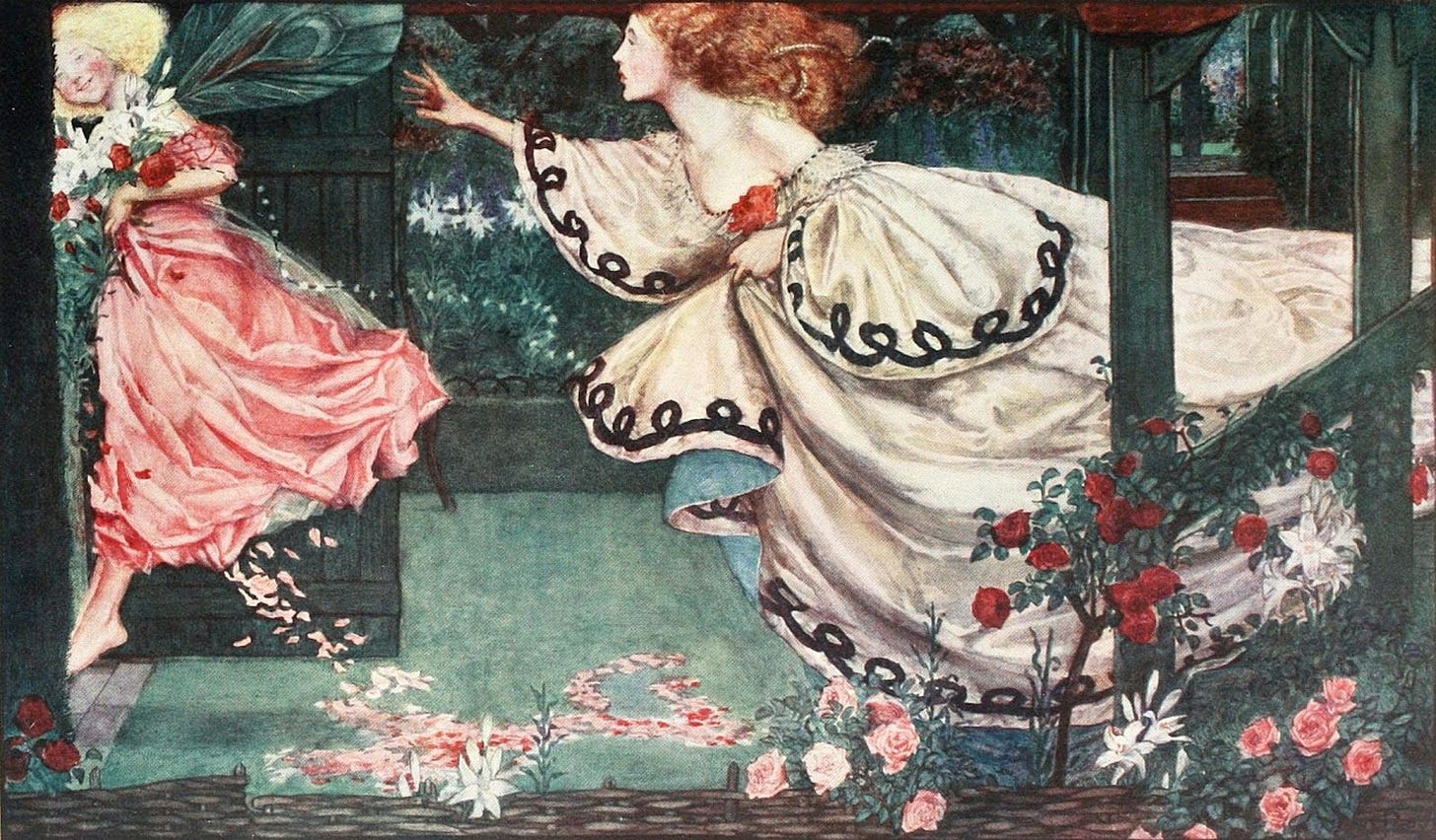

Youth and the Lady, by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale

The artificialness of living, however, feeds this kind of illusion. The lady in the above painting did not have botox or plastic surgery available yet, but while it may have made her sad to see Youth flying away, at least she would never convince herself she looked young when she looked like this:

What is uncanny in the above picture is the mix of (artificial) accidents denoting youth and accidents denoting old(er) age, plus the artifacts of plastic surgery. The poor lady does not look young, but doesn’t look wise or respectable as she would if she had allowed Time and Gravity to work on her face. And she certainly has very little to do with the gorgeous young lady she was 40 years ago:

(Yup, it’s Demi Moore. Both are; same substance, same essence, very distinct accidents)

AI, however, unlike us, cannot understand that there is an underlying substance. All it has, all it deals with, are symbols deprived of any reality. It cannot understand that there is a lady called Demi Moore, who used to be a gorgeous young lady and now is a fake-teeth-beaming inhabitant of the Uncanny Valley. It can associate the successive letters of her name and the pixels in all of her pictures, but it can’t understand that both her name and the pictures refer to someone. It sees better than we the frequency with which this or that word (or rather successive letters, or successive arbitrary binary codes) is associated with that or that other word in the texts that are around a picture bunch of pixels. It may even perceive that this or that word (say, “weird”, or “gorgeous”) is associated with the words “negative” or “positive”, without being able, however, to understand what positive or negative mean. It can only juggle symbols and seek statistical associations between them.

AI is the apex of something that started long ago, leading to the world that gave us The Matrix. A crescendo of artificialness, increasingly oblivious to reality itself, increasingly concerned with accidents, increasingly distant from what makes us human, both in essential and in accidental terms.

Duns Scotus’ mistake of denying that God’s Being-in-Himself is different from our participative being (I wrote about it in Portuguese only; as it’s quite a technical text, I wouldn’t trust mechanical translations) led to a worldview in which God can be, and is, seen as a guy with a white beard sitting on a cloud, instead of the source of both existence and order in the created universe. In turn, it led to a purely mechanical view of Creation, which led to both sides of the “humans versus ‘nature’” error I mentioned above, and to

Descartes’ error of seeing man as a ghost inhabiting a machine, and ideas as more “certain” (therefore truer and more real) than reality itself. In turn, it led to

A mathematical metaphysics, which underpins modern physics, making it much easier to reduce everything, including human lives, to mere numbers, as is done in

Ideological thinking, which oversimplifies social reality, reducing it to a few formulas, with the inevitable consequence of genocide and lesser forms of cheapening human life. Its individual equivalent is

Extreme subjectivism, which denies the real-ness of reality and reduces the other (our neighbor, to use biblical terminology) to “how they make me feel”. This is obviously much aided by

A society that Epicurus would love, in which the absence of pain and fear (for us) is the main societal goal, even if it implies suffering and terror for them. We have HVAC systems and drive electric cars, and we couldn’t care less about the kids in Africa mining lithium or the factory workers in China who sleep under the machines they operate. If we have a headache, we can pick among several different painkillers, but if someone has cancer, he will have both opioids and a hospital room in which he will be hidden from us so that we are not reminded that suffering is still possible.

All that, in a way, is nothing but different ways of running away from what things really are. We reduce our social and ecological environment to things that are neither what those environments are really composed of, nor things that exist by themselves. We reduce them to accidents: numbers, categories, abstractions that may well be present in them but are not what they are. We even managed to find a way to make Descartes’ error seem right, splitting our single substance into a body and a mind, one completely separated from the other.

If we are too fat, we’ll inject ourselves with semaglutide because it’s a “body issue”, even if the real problem is our relationship with food. While there are people whose metabolism makes it easier to get fat, the vast majority of those whose weight is way above the boundaries of health are that way because their relationship with food is deeply unhealthy.

AI is nothing more than the final de-materialization. While we can’t avoid the realization that we have bodies, even as we cling to a vehement denial that we are bodies, or rather substances that are composed of body and soul in a single being, AI doesn’t have and is not a body. It’s a “pure mind”, like in the dreams of those who talked about “uploading their minds to a computer”, or the disembodied brains floating in liquid so common in sci-fi dystopias or cartoons.

The fact that it can’t perceive reality, or even realize that there is a reality behind the symbols it so dextrously manipulates, is not a bug, but a feature. That’s precisely why it is being treated as a new Oracle of Delphos, a new savior and overlord to rule wisely over us: it can’t be “tricked” by reality if it doesn’t know that reality exists. It can agree 100% with Elon Musk when he says that “The fundamental weakness of Western civilization is empathy,” because empathy presupposes the perception that the other is real.

The fact that AI is not even able to understand what wisdom would be doesn’t matter for those who have spent their lives running away from wisdom and embracing the oversimplification of reality that ideologies offer us. It doesn’t matter that, when asked to produce a list of books to read during the summer, it hallucinates books that never existed. It may be even better that way; after all, books have the nasty quality of being often more real than reality itself, even when in ebook format.

It makes perfect sense that, at this moment in the history of Western decay, we invented the perfect autistic liar: it’s exactly what our society dreamed each of us could be.

Reading this alongside Jacques Ellul’s works offers a quite interesting perspective. I can’t help but wonder how he might analyze AI were he alive today, something like the arguments in this article.

A personal take: I was an undergraduate in Rio de Janeiro, living in suburb and commuting to the South Side daily I used to feel things were different there, 'cause those kids were laughable, living in a fantasy as if they only knew the world from their rich grandma's basement window. Reading this brought that memory rushing back.